The Dichotomy of an Immigrant Writer

I think a desire every writer has is to be understood. I’m not a fast thinker. I just don’t like to lose so I talk fast and use complex words. That’s makes me into the kind of person who will steamroll people with circular reasoning that doesn’t get noticed in the conversation.

Writing lets me take my time. I can delete the parts that show how flustered I get. The side that is unbecoming.

It’s one medium to express the thoughts I can’t in the world around me. The kind of world that thinks it’s weird that my greatest materialistic desire is a shelving unit designed by Dieter Rams.

Instead, I’ll write about it in the hopes I’m understood by someone else. But it can be frustrating when you can’t communicate your passions to those you love. Particularly the ones who brought you into the world.

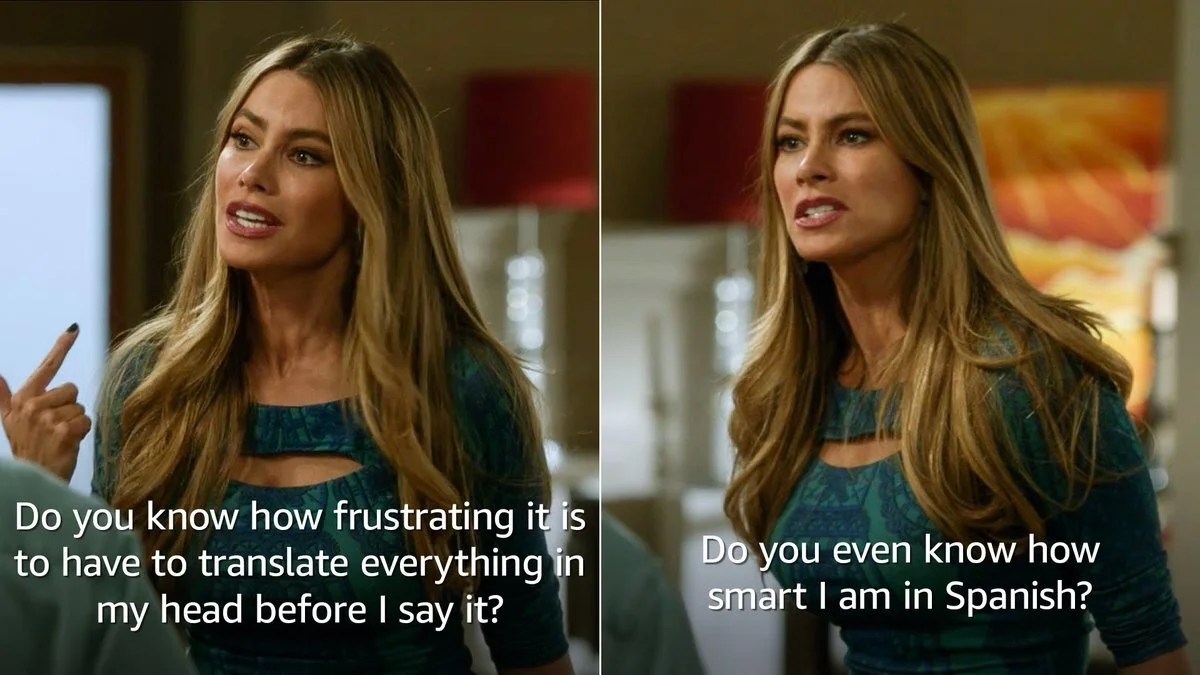

No other scene in Modern Family hit me harder than this:

That’s how I feel trying to explain business and investing in Korean when my parents get a hot stock tip about a pharmaceutical company that is “supposed” to 10x. I imagine that’s how every child of immigrant parents feel when they try to share more about something they love with their parents.

I love writing and reading about business, psychology, and philosophy. You might’ve guessed that from my essays and book list. But I find it a challenge to communicate these to friends that do not share the same interest.

It’s near impossible for me to communicate business and investing fundamentals with friends who think share prices are important, CNBC is legitimate and venture capitalists’s advice on public equity should be trusted. Oh, and that’s in English. With a language barrier, there is a multipier effect to the frustration.

That’s just one occurrence. Reading annual reports in Korean and reading Korean newspapers was one way for me to get over that hump. But with every new book I read, every new lecture I digest, every new essay I write, the gap inevitably feels like it’s widening with my parents.

It takes serious work to even maintain it. Three-hour FaceTime conversations have now become a norm as I try to explain what a newsletter is or what I used to do as an accountant or investor. Remember that I was just talking about language here. Cultural differences are another multiplier on top of that.

Consider the oddity where I’m taught in school that I have to make eye contact with people because it’s rude if I don’t. Yet, I’m taught at home not to make eye contact because it’s rude.

One benefit this gap could have is in how I write. The goal of every writer is to speak the truth. That is, what is true for me. This can be difficult for people whose parents and loved ones are both fluent in English and love to read.

I learned it’s a fear writers have that people close to them will read what they write. I realized I didn’t have that fear. Mine was related to how strangers I never met — but might meet — might think of me.

The truth is, my parents signed up for my newsletter recently. After three years of writing, I was happy to see their support in my mailing list. Though I admit, I think they’ll have a difficult time reading what I write.

It’s not just them. I think I told my closest friends I was writing a newsletter but I never asked any of them to sign up. See, most of my friends don’t like to read and a newsletter is probably akin to a foreign language to them.

Their absence in my maillist is support I would’ve liked to have had. It would be a great way to not have to answer the question “what have you been up to since last year?”. But it also means most people reading what I write don’t see me for coffee every week or know of my adolescence.

Yes, I would love it if my parents could understand everything I write and I hope they will. There’s still a part of me who is the child that wants my parents to tell me I’m smart. But a part of me is relieved that this gets to be my own space. Quite like how I don’t like talking to anyone or know anyone at the gym. It’s my space to do the work I need to do. Space where it’s easier to be honest and tell the truth.

Marco Pierre White told a story of his teacher who showed held out his palm in front of him and asked Marco what he saw. Marco said he saw a palm. The teacher said he saw four knuckles. That’s just beautiful.