The Darjeeling Limited

A Wes Anderson movie about the baggage we carry in life, the paternal shadow for young men, and the process of abandoning it.

This isn’t a movie review in the sense that I have a verdict or recommendation of it. Rather, it’s a reflection on the emotions the work invoked over my ~2-hour relationship with it.

The synopsis is about a journey three brothers undertake in India. Much of the journey happens on their train, The Darjeeling Limited. I admit, my love for rails may have influenced the level of affection for the film. A love that results in the forgoing of minor sins (not just in a movie but in life too).

What becomes apparent through the movie is the poor relationship between the siblings, their estranged mother, and the trio’s lack of closure to the death of their father. It’s possibly the application of the Freudian teaching of how young men only achieve true independence of self when the paternal figure dies. A concept that seems to manifest uniquely in each son’s life.

Francis (Own Wilson’s character) is the eldest who appears to struggle with control and insecurity for attention, possibly stemming from a mother who continuously abandons the trio. Peter (Adrien Brody’s character) is the middle child who is running from the fatherhood of his own having left his 7-month pregnant wife to join Francis’s adventure (despite not being a big fan of his elder brother). Jack (Jason Schwartzman’s character) is the youngest who writes stories based on his personal experience yet denies this fact and insists all characters and situations are purely fictional.

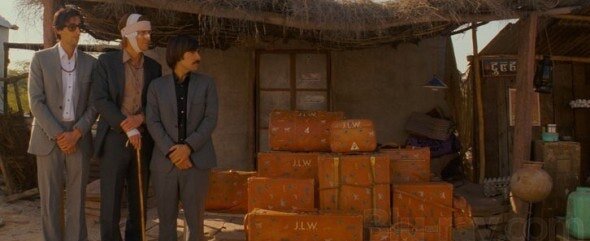

If the brothers’ character trait of struggling with their individual insecurities wasn’t so clear, Anderson makes it a point to have the trio carry a few dozen suitcases (what I take to be emotional baggage) everywhere they go.

Here:

And here:

And here:

You get the idea.

They are literally carrying bags around everywhere they go. Specifically, a set of suitcases owned by their father (the monogram of J.L.W on all the suitcases is their father).

So, despite the various snafus the trio get into throughout their journey, they continue to hold onto the inconvenient caseloads of baggage that seem to symbolize an inability to let go of their father. This possibly points to the Jungian behaviour of not being able to shed the symbolic effects of the paternal figure. Their father has passed (Freudian independence should’ve been achieved) but they’ve failed to claim their independence, preferring to stay in the shadows of the suitcase (unable to move away from the symbolic father per Carl Jung).

The story eventually reaches a point (spoiler alert, seems redundant now though) where the brothers find their mother hidden away in the Himalayas. They confront her for not coming to their father’s funeral and going AWOL from their lives.

The day after being confronted, she disappears, leaving the brothers once again without a mother in their lives. But this time, the abandonment brings closure where the symbolic figure of the mother dies with the realization that she is just another human. Not the god-like deity they came to revere her as but a normal and flawed human like themselves.

In a way, it seems the brothers had been using their mother as a lighthouse to guide them through the storm only to realize they need to get out of the cloud of their father’s absence themselves. The story concludes with the brothers successfully letting go of their father. They literally abandon the dozens of suitcases with their father’s initials on the train platform as they board a new train to continue their adventure.

The final scene of embarking on a new adventure without their father’s suitcases appears to be each sibling’s willingness to participate in the journey of figurative self-acutalization. Francis learns to let go of desires to control and being the center of everything and earns the trust of his siblings as a result. Peter embraces fatherhood. Jack accepts his stories are based on his life experiences.

I feel crass saying this is a “coming of age” story as I don’t know what Anderson intended but it has that effect. As someone who is caught between the worlds of Western individualism and Eastern familism, it’s a story that shines a light on my Western mind’s journey to independence while the Eastern half struggles with the perceived dishonouring of one’s moral duty. I doubt this is a struggle unique to myself but the Jungian logic of merely realizing one’s parents are normal, flawed humans like myself, seem too simple a feat to undo centuries of ingrained Confucian philosophy.

Still, it doesn’t mean one gives up and The Darjeeling Limited is one that continues to give me hope on my own journey.